Stories

Nancy Altman Testifies at U.S. House Hearing on Retirement Security

Statement of Nancy J. Altman[1], J.D., President of Social Security Works

HEARING ON IMPROVING RETIREMENT SECURITY FOR AMERICA’S WORKERS

United States House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means

February 6, 2019

Chairman Neal, Ranking Member Brady, and other members of the Committee:

Thank you for holding this crucially important hearing on improving retirement security for America’s workers. Too often, discussions of employer-sponsored retirement arrangements take place compartmentalized from discussions of Social Security. I commend the Committee for taking this broader, more comprehensive look. As the Committee requested, my statement focuses on the importance of Social Security.

Social Security has Transformed the Nation

Prior to Social Security, Americans inevitably found themselves unemployed, unable to continue to work as they aged. In those circumstances, they routinely moved in with their adult children. Those who had no children or whose children were unable or unwilling to support them typically wound up in the poorhouse.

When Social Security became law, every state but New Mexico had poorhouses (sometimes called almshouses or poor farms). The vast majority of the residents were elderly. Most of the “inmates,” as they were often labeled, entered the poorhouse late in life, having been independent wage earners until that point. A Massachusetts Commission reporting in 1910 found, for example, that only one percent of the residents had entered the almshouse before the age of 40; 92 percent entered after age 60.

Social Security made independent retirement a reality. Prior to its enactment,the verb “retire” did not mean what it means today. It was generally used to refer to withdrawing temporarily, as, for example, to retire to the bedroom at the end of the evening. The first known usage of the noun “retiree” was in 1935, the year Social Security was debated in Congress and enacted into law. It was only in the 1940s, once Social Security started to pay monthly benefits, that the word “retiree” became commonly used.

Social Security is the Foundation of the Nation’s Retirement Income System

The nation’s patchwork system of retirement income is largely an historical accident. Shortly after Social Security was enacted and expanded to include benefits for dependents, the nation entered World War II. During the war, Social Security benefits were not increased and consequently eroded in value.

During the Depression and war years, the federal government substantially increased income taxes, and, in response, business owners created pension plans as “tax-avoidance mechanisms,” as they were called at the time.[2] Moreover,the government imposed wage and price controls during World War II. The controls, however, applied only to current compensation, not to private pension arrangements or other forms of deferred compensation. Consequently, employers offered private pensions as a way of competing for labor made scarce by the demands of the war.

Following the war, Congress, now controlled by Republicans, failed to increase Social Security benefits. At the same time,unions began to bargain aggressively for pensions. As a result of all these factors, Social Security benefits eroded during the 1940s, while employer-sponsored pension plans grew substantially.

It was during this period that the metaphor of a three-legged stool to describe the nation’s patchwork retirement income system was first used. It was coined in 1949 by Reinhard Hohaus, a prominent actuary who worked for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

The metaphor was a useful image for Metropolitan Life and others promoting private pensions, but it was never accurate, because the legs were never equal. Even for workers fortunate to have employer-provided pensions and personal savings to supplement their Social Security,their Social Security benefits have generally been the most important and secure source of retirement income. A more apt image of the nation’s retirement system, therefore, is the pyramid below:

Social Security is the Most Important Part of our Retirement Income System

As the image of the pyramid conveys, Social Security is the solid base upon which fortunate workers have been able to build. Social Security is unquestionably the most important source of retirement income for the nation’s working families, even those fortunate to have other assets.

Though the wealthiest among us may not recognize Social Security’s importance to them, they might be enlightened by the cautionary tale of Neil Friedman, a millionaire who invested his entire fortune with Bernie Madoff. When Madoff’s Ponzi scheme was revealed, Friedman and his wife found themselves forced to survive on their Social Security and money they could earn selling note cards emblazoned with photos of their former lavish vacations. Moreover, the Friedmans were not the only Madoff victims left destitute.

Like those Madoff victims, about one out of three retirees depend on Social Security for virtually all of their income. Around two out of three retirees depend on Social Security for the majority of their income.

As important as Social Security is for virtually all of us,it is especially important to women, people of color, those who are LGBTQ, and others who have been disadvantaged in the workplace. Those groups are less likely to have jobs with employer-sponsored pensions. On average, they have lower earnings and therefore less ability to save. They are more likely to have health problems and physically demanding jobs that force early retirement. Also, they are more likely to have periods of unemployment or take time out of the paid work force to work as family caregivers. Moreover, because women and Hispanics have, on average, longer life expectancies, they have even greater need of Social Security’s guaranteed benefits that last until death.

Almost one out of two divorced, widowed or never-married female beneficiaries aged 65 and older rely on Social Security for virtually all of their income (46 percent in 2016).More than one out of two unmarried African American beneficiaries aged 65 and older rely on Social Security for virtually all of their income (55 percent in 2016). For Hispanic Americans the percentage is even higher. Nearly six out of ten unmarried Hispanic beneficiaries aged 65 and olderrely on Social Security for virtually all of their income (58 percent in 2016).

African Americans and Hispanics disproportionately qualify for Social Security disability and survivor benefits, as do their children. African American children constitute 14 percent of all American children, but 22 percent of the children receiving benefits as the result of a parent with a disability and 21 percent of the children receiving benefits as the result of the death of a parent.

Social Security is the Nation’s Most Universal, Efficient, Secure, and Fair Source of Retirement Income

Social Security’s importance and success derive from its essential purpose and ingenious design. It is insurance against the loss of earnings in the event of old age, disability, or death. Insurance is most cost-efficient and reliable when the risks can be spread across as broad a population as possible and when no one can purchase the insurance when personal risk factors increase – a practice known as adverse selection. The only entity that has the power and ability to establish a nationwide risk pool that covers all workers at the moment they start work and, in that way, avoids adverse selection is the federal government. It is the only institution that can make the insurance mandatory and universal.

Social Security is, of course, mandatory and nearly universal. Nearly nine out of ten seniors receive Social Security retirement benefits. Around 175 million workers contribute to Social Security.

For the same reasons, Social Security is extremely efficient. Moreover, when the federal government administers the insurance, overhead is minimized. Instead of high-paid CEOs, hardworking civil servants are in charge, and other costs, like advertising and marketing, are unnecessary. Consistent with that predictable efficiency, less than a penny of every Social Security dollar is spent on administration. The rest – more than 99 cents of every dollar – is paid in benefits. That extremely low administrative expense is unachievable by employer-sponsored retirement plans or private insurance.

Social Security has other attributes that add to its value and importance. Like employer-sponsored defined benefit plans, its benefits are pegged to final pay.] That is important because replacing final pay in order to maintain one’s standard of living in retirement is the goal. Also like employer-sponsored defined benefit plans, Social Security benefits are paid in the form of joint and survivor annuities. Consequently, they last until death, in contrast to savings, which can be outlived.

In addition, Social Security’s guaranteed benefits are extremely secure. They are much more secure than retirement savings, which can be lost as the result of a market downturn or simply poor or unlucky investment decisions. They are also much more secure than employer-sponsored traditional pensions and much more secure, as well,than the life insurance, disability insurance, and retirement annuities sold by private insurance companies. Unlike private sector retirement plans and insurance products, Social Security is sponsored by the federal government,which is permanent, and so will not go out of business. It has the power to tax and issue bonds backed by the full faith and credit of the nation. Furthermore,all risks are spread nationwide, not concentrated on single employers,insurance companies, or worse, individual workers.

Moreover, unlike savings, the benefits are only available when an insured event occurs and cannot be withdrawn to meet more immediate needs. Contributors understand that the benefits are only payable as a result of disability, death, or old age. They do not expect or seek early withdrawals or lump-sum payouts. In addition, the benefits are protected from private-sector creditors. Consequently, they are efficiently targeted, certain to be paid only in old age or when an insured worker becomes disabled or dies.

In contrast to employer-sponsored defined benefit plans, Social Security is completely portable from job to job. Consequently, it is as good for mobile workers as it is for workers who remain with one employer.

Also, Social Security imposes fewer administrative costs on employers. It is carried from job to job; records are kept seamlessly by the Social Security Administration through the use of Social Security numbers. Wages from all covered employment are automatically recorded by the Social Security Administration and used in the calculation of benefits. Employers are free from the record-keeping,reporting, and fiduciary requirements of their own sponsored plans.

Of course, Social Security provides for more than retirement. Its benefits are payable in the event of disability, if that occurs prior to retirement, and in the event of death, if there are eligible survivors. Indeed, as a result of these provisions, Social Security is the nation’s largest children’s program.

Furthermore,Social Security includes features that are not found in private sector alternatives. For example, private sector annuities and defined benefit pensions reduce the annuity amount of the primary insured, if a spouse is added. In contrast, Social Security’s annuities automatically include add-on benefits for the joint and survivor portion of the annuity without reducing by a penny the life annuity portion paid to married workers.

If the worker has been divorced after having been married ten years, there are add-on spouse and widow(er) benefits for every ex-spouse. Again, those add-on benefits don’t reduce the worker’s retirement, disability, and family benefits by a penny. Importantly, those divorced spouse and widow(er) benefits are the ex-spouse’s as a matter of right. The parties to the divorce are spared the burden of having to negotiate or go to court to secure their benefits.

Similarly, the benefits Social Security provides to children when adults supporting them lose wages as the result of death, disability, or old age, are, like spousal and widow(er) benefits, add-on benefits that do not reduce by even a penny the primary insured’s benefits.

Importantly, all benefits are annually increased to offset the effects of inflation. Social Security provides inflation protection without limit, regardless of the rate of that inflation. Consequently, unlike traditional private pension benefits which erode over time, Social Security maintains its purchasing power. (It should be noted that the measure of inflation is in need of updating to make it more accurately reflect the costs of beneficiaries, but, even so, the availability of uncapped inflation protection is one of Social Security’s most valuable attributes.)

Social Security’s One Shortcoming is that its Benefits are Too Low

As vital and well-designed as they are, Social Security’s benefits are extremely modest by virtually any measure. In absolute terms, the average monthly Social Security benefit in December 2018 was $1,342, or $16,104, on an annualized basis. That is below the 2019 official federal poverty level for a two-person household, and substantially below the amount needed to satisfy the Elder Economic Security Standard Index, a sophisticated measure of the income necessary to meet bare necessities.

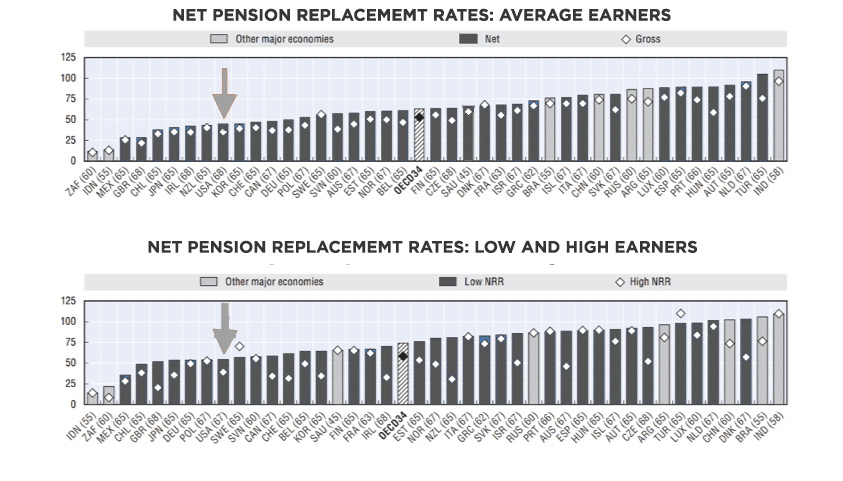

Social Security’s benefits are also extremely low compared to the retirement benefits of other industrialized nations,as the following chart reveals. (The bars designating U.S. benefits are highlighted with arrows.)

Social Security Replacement Rates in OECD Countries by Earnings Level

As informative as are Social Security’s absolute benefit levels and its levels compared to other nations’ benefits, the most important measure of the inadequacy of Social Security’s benefits is what proportion of pay is replaced, since replacing lost wages is the goal of the program.

Experts estimate that workers and their families need about 70 to 80 percent of pre-retirement pay to maintain their standards of living. Those with lower incomes need higher percentages; those more affluent, with more discretionary income and other assets, need somewhat less.

While Social Security appropriately replaces a larger proportion of pre retirement pay of workers who have lower wages, it does not come closeto providing sufficient income to meet the goal of maintaining standards of living in retirement. Workers earning around $50,000, who retired at age 62 in 2018, received only 32 percent of their pay or about $16,000 a year. Lower-income workers, earning around $22,500, received around 43 percent of their pay, but that is only about $9,700 a year.

Social Security Will Be Even More Important in the Future, But its Benefits Will be Even Less Adequate

Numerous polls and surveys over recent years reveal that worry about not having enough money in retirement leads the list of Americans’ top financial concerns. A Gallup poll conducted last May, for example, reported that nearly six out of ten Americans – 58 percent – were very or moderately concerned about “Not having enough money in retirement.” That topped six other financial challenges, including “Not having enough money to pay for your children’s college” and “Not being able to pay your rent, mortgage or other housing costs,” and tied with “Not being able to pay medical costs in the event of a serious illness or accident.”

Expert analyses make clear that Americans’ concerns about retirement are well founded. The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College (“CRR”), for example, has, for a number of years, calculated a National Retirement Risk Index. Its most recent analysis found that one out of two working-age households will be unable to maintain their standards of living in retirement even if they work until age 65, take out a reverse mortgage on their homes and annuitize all of their other assets. CRR has found that the number of “at risk” working-age households increases to over 60 percent when health care costs are taken into account.

The reasons for our retirement income crisis are clear. Traditional employer-sponsored defined benefits are disappearing. In 1980,around 38 percent of workers participated in defined benefit plans; in 2017,only 15 percent did. Many employers have replaced traditional defined benefit plans with 401(k) plans, but those have proven inadequate for all but the very wealthiest.

As a result of these developments, future retirees are likely to rely on Social Security for even more of their retirement income. However, as reliance is growing, the Social Security foundation is gradually weakening.

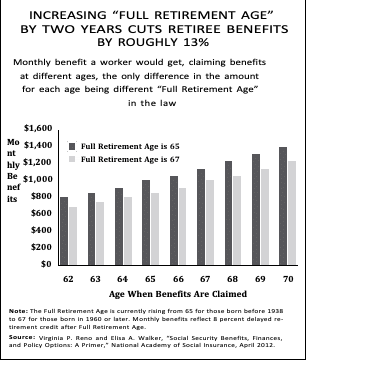

As inadequate as the percentages of pre retirement earnings that Social Security replaces are today, they will be lower in the future as the result of current law. In 1983, Congress passed legislation that raises Social Security’s full retirement age from age 65 to 67, a change that is still being phased in.(It will be fully phased in for those born after 1959.)

It is facile – but wrong – to think that if the retirement age is increased and you work longer, you will catch up. For those not thoroughly immersed in how Social Security benefits are calculated, increasing Social Security’s “full” retirement age may sound like just a small, reasonable adjustment for changes in life expectancy. But that is incorrect.

Raising Social Security’s statutorily-defined“retirement age” by a single year is mathematically indistinguishable from about a 6 to 7 percent across-the-board cut in retirement benefits, whether one retires at age 62, 67, 70, or any age in between. If the definition of “retirement age” is changed to be an older age, you always get less than you would have without the change, as the chart below illustrates.

Cutting benefits by raising the statutory retirement age is especially hard on low-wage workers (disproportionately people of color) who are more likely to work in physically demanding jobs, as well as on workers (disproportionately women) who must retire early to care for aged parents or other family members.

In addition to understanding that raising the statutory retirement age is identical to an across-the-board benefit cut because of the manner in which benefits are calculated, it is also important to recognize that those urging this particular form of cut have exaggerated the gains in longevity and ignored the fact that those gains have not been equally distributed.

Although people, on average, are living somewhat longer today, the increase is not the decades that some claim. Moreover, in the last three years, life expectancy from birth in the United States has declined. Furthermore, these are average increases across the population. The gap between the life expectancies of higher-income and lower-income Americans is growing.

Those who want to cut Social Security by increasing the statutorily-defined “retirement age” focus on increased average longevity to push the simplistic belief that an aging population makes Social Security unaffordable. The population is indeed aging, but that is primarily because birth rates are low, not because of rapidly increasing life expectancies, according to the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration.

It is important to recognize not only that the population is aging but also to understand the reason why.Because it is caused by lower birth rates, increased immigration is an obvious solution. Because immigrants to the United States tend to be younger and may,as a matter of culture, have larger families, they increase the ratio of working age population to retirement age population in much the same way as higher fertility rates do.

In Congressional testimony, the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration explained the benefit to Social Security of increased immigration:

“Immigration has played a fundamental role in the growth and evolution of the U.S. population and will continue to do so in the future. In the 2014 Trustees Report to Congress, we projected that net annual immigration will add about 1 million people annually to our population. With the number of annual births at about 4 million, the net immigration will have a substantial effect on population growth and on the age distribution of the population. Without this net immigration, the effects of the drop in birth rates after 1965 would be much more severe for the finances of Social Security, Medicare, and for retirement plans in general.”

Raising Social Security’s statutorily-defined “retirement age” will substantially weaken the retirement security even of workers who can and want to remain in the work force: Despite the existence of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, older workers have a much harder time finding new work after being laid off. With no job prospects, they may find themselves with no choice but to claim permanently reduced early retirement benefits at age 62, even if they wish to work longer.

The nation is now in the middle of seeing the full retirement age rise to 67—a 13 percent across-the-board benefit cut. It would be the height of irresponsibility to contemplate more changes in the same direction before the current benefit cut is fully phased in, and its impact on low-income workers, women, minorities, and everyone else has been carefully assessed.

An additional reason that Social Security benefits will likely be less adequate in the future without Congress legislating any changes is because of increasing Medicare premiums, which are generally directly deducted from Social Security benefits. At a time when today’s workers will likely be more dependent on Social Security, its benefits will, without legislation,replace smaller and smaller percentages of pre-retirement earnings.

Important Understandings About Social Security When Preparing to Legislate

Whether to Increase or Cut Social Security’s Modest Benefits is a Question of Values, Not Affordability

Social Security is extremely affordable. As the next chart makes clear, Social Security’s cost as a percentage of GDP is close to a straight horizontal line for the next three-quarters of a century and beyond.

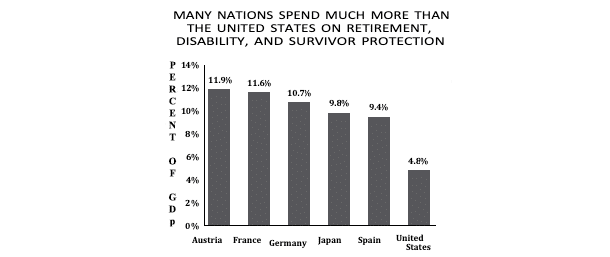

At the end of the 21st century, Social Security is calculated to cost 6.16 percent of GDP. That is a lower percentage of GDP than many other industrialized countries spend on their counterpart programs today:

Moreover, our nation is projected to be much wealthier at the end of the 21st century, just as we are wealthier now than we were seventy-five years ago, before computers, smartphones, and other technological advances. That means that the 5 to 6 percent of GDP will be easier to afford in the future, just as 10 percent is a larger amount, but more easily afforded, if you are earning $100,000 than if you are earning $10,000. In one case, you have$90,000 remaining; in the other, just $9,000.

Nor should the increase of just over one percent of GDP be difficult to absorb. To put that projected increase in perspective, military spending after the 9/11 terrorist attack increased by over one percent of GDP, as a result of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars—and that increase was the result of a surprise attack, with no advance warning. Similarly, spending on public education nationwide increased by 2.8 percentage points of GDP between 1950 and 1975, when the baby boom generation showed up as schoolchildren, without much advance warning.

Social Security is Insurance, Not Welfare: Means-Testing it Would Radically Change it

It is also imperative that Social Security be seen as the insurance that it is. Some treat it as if it were welfare and argue that it should not go to those who don’t “need” it. As part of the argument, they urge that Social Security be means-tested. That would fundamentally change what Social Security is.

It is unsurprising that some confuse Social Security and welfare because it is among the nation’s most effective anti-poverty programs,but that is a byproduct. Welfare programs are designed to alleviate poverty;Social Security and other insurance are designed to prevent beneficiaries from falling into poverty in the first place.

Social Security is part of workers’ compensation. It is a benefit that workers earn. Welfare requires recipients to demonstrate something negative about themselves: that they have so little income and assets that they are in need of the community’s help. In contrast, Social Security beneficiaries are asked to demonstrate something positive: that they have worked and contributed long enough to have earned their benefits.

Creating a means test, even if it were set at $1 million,would transform Social Security by requiring people to prove that they aren’t that wealthy. That would destroy the very essence of the program.

The nation already has means-tested welfare for seniors: the Supplemental Security Income program, financed from general revenue. SSI has eroded and should be increased, particularly by those proposing means-testing Social Security, if they are sincere about helping the most vulnerable among us. What should not happen, though, is the radical transformation of Social Security into a second SSI program,transforming it from insurance to welfare.

Social Security is Insurance, not Forced Savings

Benefits Should Remain Guaranteed, Not Subject to the Vagaries of the Stock Market

Similarly, some treat Social Security as if it were forced savings. They seek to convert its guaranteed benefits into a savings account. Everyone should save, if they possibly can. Everyone should also have adequate insurance. Savings are necessary for short-term emergencies and expenses; insurance is prudent for economic losses that are predictable for groups, but unpredictable for individuals, such as premature death, disability, or extreme longevity. Both insurance and savings are needed for economic security. Savings have their own strengths, but those strengths are not marks of their superiority to insurance. Savings are different from,but not superior to, Social Security or other insurance.

It is important to recognize that the higher rates of return that can be obtained through investment in equities could easily be obtained, on a collective basis, through Social Security, without affecting its basic structure of specified, guaranteed benefits, if that is what the American people favored.

Having Social Security diversify its portfolio is starkly different from individuals who invest retirement funds in the stock market. When individuals do so, they take a substantial risk. They bear the entire risk of poor investment performance. In addition, they have the risk of being forced to sell when the market is down. They ordinarily will have to cash in their investments at or near the time of retirement and, if they are to protect themselves from running out of money before they die, will need to purchase annuities, which makes the saver unable to recoup investment losses. In other words, individual investors have limited time horizons. Their retirements may not time well with the ups and downs of the stock market.

In contrast, a well-managed, diversified Social Security portfolio would never be in a position of having to reduce net assets at any particular time and so could ride the market’s ups and downs. Investment risks would be spread over the entire population and be independent of the time a worker filed for benefits. Retirement income would continue to be based on earnings records, not the vagaries of the stock market.

To repeat: Insurance, not savings, is what is needed to prepare for the possibility of substantial financial losses which are predictable for groups but unpredictable for individuals – like living to age 110, or becoming disabled, or dying prematurely, leaving dependent children. Social Security protects against all those risks.

To manage the risk of the financial loss associated with the loss of a home as the result of fire, homeowners purchase fire insurance; they do not simply save for the contingency. Similarly, car owners have car insurance, not car-accident savings accounts. And to manage the risk of lost income as the result of disability, death, or old age, wage insurance like that provided by Social Security is essential. To be economically secure, everyone who works for wages needs wage insurance in the form of Social Security and unemployment insurance.

Social Security Embodies the Best of American Values

Social Security has been so successful and popular because, from the beginning, it has embodied core American and religious values. It rewards hard work. The more workers earn and contribute, the higher their benefits. At the same time, in recognition that those who earn less have less discretionary income, it replaces a higher percentage of first dollars earned. It is prudently managed and responsibly financed. Social Security can only pay benefits if it has enough income to cover every penny of its cost, including the cost of administration. It cannot borrow or deficit-spend. As a result, Social Security does not add a penny to the government’s annual deficits or accumulated debt.

In a message to Congress proposing the expansion of Social Security, President Eisenhower captured the essence of the program:

“Retirement systems, by which individuals contribute to their own security according to their own respective abilities … are but a reflection of the American heritage of sturdy self-reliance which has made our country strong and kept it free; the self-reliance without which we would have had no Pilgrim Fathers, no hardship-defying pioneers, and no eagerness today to push to ever widening horizons in every aspect of our national life. The Social Security program furnishes, on a national scale, the opportunity for our citizens, through that same self-reliance, to build the foundation for their security.”

In working toward the important goal of improved retirement security for workers, it is crucial that Social Security be recognized as the essential program that it is. It is imperative that members of this Committee understand its basic structure, as well as the guiding principles and values that underlie that structure. That will guarantee that your actions will increase, not reduce the retirement security of the nation’s working families now and in the future.